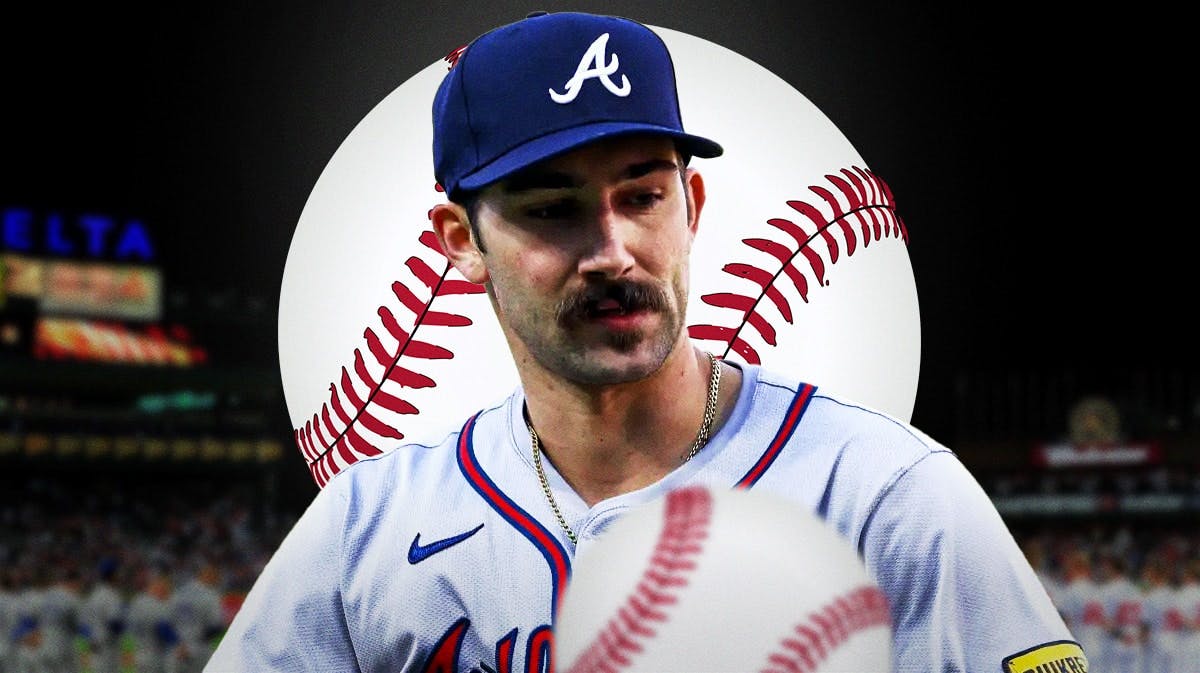

The Atlanta Braves have lost strikeout pitcher Spencer Strider for the 2024 season after receiving surgery on a torn UCL in his pitching elbow last week.

However, Atlanta’s release has some news: Strider had a “internal brace” for his revision instead of the typical UCL repair method. To learn more about what this implies for Strider and how the internal brace surgery differs from the usual “Tommy John” UCL reconstruction, Braves Today contacted the New York-based Hospital for Special Surgery and spoke with an expert.

One of the most important lessons from our conversation with Theodore A. Blaine, MD, a sports medicine surgeon at HSS, is how hard a second surgery on a pitcher’s pitching elbow is – there is no straightforward pattern for what to do, as each case is unique.

“The decision to perform a UCL reconstruction (“Tommy John” surgery) or a UCL repair (with or without an internal brace) or both is based on many factors,” Blaine told us, with “each of these […] weighed to determine the best options for each individual.” It is also a significant list of factors. “The age of the player, the location of the injury to the UCL, the desired activity level of the athlete moving forward, the quality of the tissue, and any prior elbow injury history are all factors that must be considered.”

However, the use of the internal brace for Strider is noteworthy; while the literature is not yet settled, there is hope that the internal brace’s presence will assist reduce future joint deterioration. “At the professional level, we are still evaluating the effectiveness and longevity of UCL repairs and reconstructions with an internal brace. However, biomechanical studies have shown that using the internal brace to enhance the UCL reconstruction results in greater strength and decreased load to failure.”

The internal brace has been fairly popular at lower levels, with high school and college players returning “in about half the time than patients who have a (traditional) reconstruction.”

As we detailed in our initial post on Strider’s operation, the standard reconstruction uses a donor tendon, usually from the patient’s forearm or a cadaver, to replace the damaged UCL in the joint. In contrast, the internal brace is a tape-like suture that is fixed into the humerus (the top bone of the arm) and ulna (the forearm), and it remains in place even after the athlete returns to play.

Blaine said that there are various risks associated with a second surgery, including “the way the initial surgery was performed, (which could) affect the options available for revision surgery.” Even if successfully performed, scar tissue can complicate the surgical technique, and bone loss on the ulna, humerus, or both may limit alternatives for new graft placement.”

Even the graft used can change matters, with the ideal being a forearm tendon – referred to as a “palmaris tendon autograft” by Blaine – although hamstring tendons are also utilized, necessitating changes to the rehabilitation program following surgery.

The two most important lessons from Dr. Blaine were the higher risk associated with a second revision and how to avoid or lessen the necessity for these surgeries in the first place.

Return to play after a second repair, sometimes known as a revision, has been less usual, according to Blaine, with rates ranging “from 65% to 78% in some studies”. A primary UCL reconstruction, the athlete’s first repair treatment, has a reported return-to-play percentage of 84-95%, owing primarily to the aforementioned aggravating variables.

But how do you prevent that from happening? According to Blaine, there isn’t much that can be done alone at the big league level to prevent the recent surge of UCL injuries. “UCL is an overuse ailment, and prevention should begin early in an athlete’s career (little league baseball) with proper pitch counts, rest days, and pitching breaks. Players should receive proper pre- and post-game treatment to limit the risk of injury and allow them to perform at their peak for as long as possible. […] These regulations should be strictly followed in order to preserve the health of young throwers. He did, however, add that “even at the Major League level, similar rules should be applied.”

According to Blaine, additional measures can be implemented for players who are at high risk for UCL injuries or have undergone prior UCL reconstruction, such as “limiting (the) number of pitches by pitch count (and) reducing the number of fastball pitches thrown by players both before and after UCL surgery,” as well as moving players from starting to relief roles to increase position longevity.

Braves fans are familiar with the concept of changing a starter to a reliever due to injury, as Hall of Fame pitcher John Smoltz did so following his 2000 Tommy John surgery. It was also a success, with Smoltz leading all of baseball with 55 saves and placing third in Cy Young voting as a reliever in 2002 before returning to the rotation in 2005. He is the first pitcher to have Tommy John surgery and be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, as well as the only pitcher in MLB history to win more than 200 games while also recording 150 saves, with 213 wins and 154 saves.

Blaine finds the introduction of new technology to be an intriguing development, as it allows teams to track the specific characteristics of pitches in real-time and biomechanically analyze pitching mechanics, velocity, and other factors that could identify what a pitcher is doing on the mound in greater detail. According to Dr. Blaine, this research “should provide even more information to teams on the types and numbers of pitches that are appropriate to protect the UCL both pre-and post-surgery in players.”

Let’s hope that baseball gets it out soon.

Leave a Reply